Summer research examining how satellite constellations affect astronomy

Randolph’s Summer Research Program is a competitive, paid program that gives students the chance to work closely with faculty members conducting research in their areas of interest. This story is part of an ongoing series featuring the work being done on campus this summer.

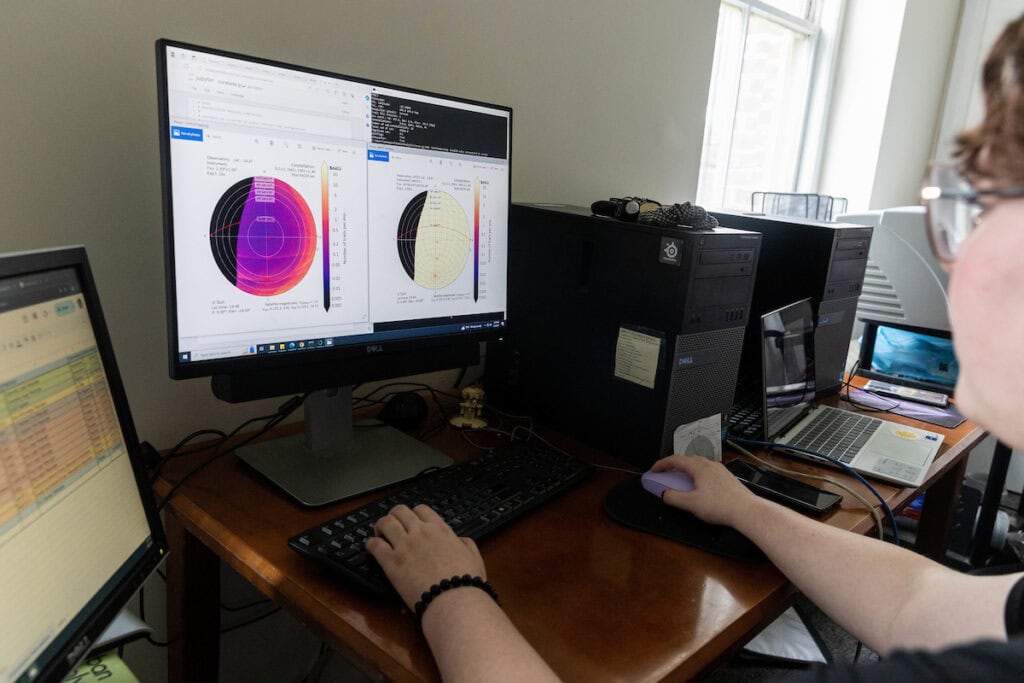

Luke Chapman ’25, professor Katrin Schenk, and Shauna Shepard (pictured) along with professor Peter Sheldon (not pictured) are developing a predictive model that will estimate the progressive degradation of astronomical images over time based on the number of satellites in Earth’s orbit.

When Shauna Shepard ’25 first started reading about how satellite constellations affect astronomical observations, she thought the problem was overhyped.

A satellite constellation is a network of satellites working together to deliver a global service—like internet or communications—from space. As satellites are launched into the sky, they leave traces of their transit on astronomical images, decreasing the scientific value of those images.

“After doing some research, I realized just how many lower orbiting satellites they are looking at putting up,” said Shepard, a physics major. “It’s a real issue faced in the astronomy community.”

This summer, Shepard is working with Luke Chapman ’25 and professors Katrin Schenk and Peter Sheldon to develop a predictive model that will estimate the progressive degradation of astronomical images over time based on the number of satellites in Earth’s orbit.

There are 10,000 satellites currently in the sky, with a whopping 500,000 proposed, based on data they’ve pulled from the International Telecommunications Union.

“It’s unlikely they’ll actually get close to that number of satellites, but it is what these companies have asked to put up,” said Shepard. “We are looking at every satellite they want to put up and incorporating the new data into a model.”

Chapman, a mathematics major and physics minor, is building a model that will map the satellites’ distribution.

“We also want to introduce a time factor, thinking about how many of these images are actually going to be ruined over a specific amount of time,” he said. “This is a very empirical, practical thing to build a model out of. It just falls into what I consider my wheelhouse, my area of study.”

The most recent data on the number of proposed satellites was collected in 2021.

“The three years matter a lot,” Shepard said. “Starlink is launching new satellites every three weeks and has been since 2019. Even in just a year, there’s an appreciable difference. We’ve seen changes to the data we’re pulling from when we started this to now.

“We‘ve already noticed there’s a disproportionate effect on telescopes that see a wide view of the sky or telescopes that take longer images,” she added. “If we can update the model’s parameters to be better, then hopefully our results will be much more accurate, and we’ll have more of a foundation to go on.”

Tags: astronomy, Class of 2025, faculty student research, Katrin Schenk, mathematics, Peter Sheldon, physics, Science Matters, SRP 2024, summer research, summer research 2024