Etched into history: Long list of esteemed alumnae included on new Virginia Women's Monument

The Virginia Women’s Monument in Richmond, Virginia

The new Virginia Women’s Monument in Richmond, Virginia, is a beautiful testament to the women who helped shape the state’s history. Among the 230 names engraved into the glass Wall of Honor are notable Virginians, such as Martha Washington, Pocahontas, Anne Spencer—not to mention nine distinguished alumnae and faculty of Randolph-Macon Woman’s College.

“These women reflect the range of accomplishments and contributions made by Virginia women across four centuries,” said Sandra Treadway, the librarian of Virginia. “They include women from all walks of life and all parts of the state. The names were chosen from a larger list of several hundred women, so to have made the final cut suggests the importance of a woman’s accomplishments in the context of her day and time.”

In order to be included, women must have lived the majority of their lives in Virginia, been deceased for at least 10 years, and made significant contributions to the region, state, or nation. Fundraising for the project is ongoing, and a formal dedication ceremony was held this fall. Treadway noted that nominations are still being accepted, and more names will be added over time.

For the College to have nine alumnae and faculty’s names engraved on the wall, Treadway added, speaks to the significant role the institution played in educating women in the late-19th and early 20th centuries.

“Randolph [then R-MWC] provided young women a rigorous and challenging education and prepared them well for whatever path in life they wished to follow,” she said. “Even during times when opportunities for women were much more limited than they are today, many Randolph-educated women had the confidence in themselves and their abilities to step out into the world and make a difference.”

Here’s a look at the nine alumnae and faculty included on the wall:

Meta Glass (Class of 1899)

Meta Glass (Class of 1899)

Born in Petersburg in 1880, Glass was a renowned classics scholar and educator, serving on the faculty at R-MWC, Columbia University, and as the third president of Sweet Briar College from 1925-1946.

A highly regarded educator, she was most known for her work as Sweet Briar College’s president. That school underwent a period of significant development under Glass’s leadership. Entering her role as president just before the Great Depression and working with limited resources, Glass was credited with keeping Sweet Briar financially viable and ensuring no faculty members were laid off or went without pay during the economic downturn. She also made a name for herself nationally, serving as president of the Association of American Colleges and the Association of University Women.

Prior to her teaching and administrative career, she attended Cornell University, earned a Ph.D. from Columbia University, and was a member of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society. She later earned honorary degrees from the University of Delaware, Mount Holyoke College, D.C.L. (the University of the South), Brown University, Williams College, Wilson College, and the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. During World War I, she served as secretary of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) in France and later as the dean of a training school for European women in Paris, working with the World’s Community YWCA. In 1920, she was awarded the Reconnaissance Francaise (Medal of French Gratitude) from the French government for her efforts. She served on the National Committee on Education and Defense from 1940-1942, and during World War II served as a member of the advisory education council of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, helping establish standards for the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES). Following the war, she was one of three delegates at the first post-war council of the International Federation of University Women in London.

After her retirement she lived in Charlottesville, where she passed away in 1967.

Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne Lewis Otey (Class of 1900)

Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne Lewis Otey (left) (Class of 1900) and her mother pictured at a suffrage rally. Credit: Blackwell Press

Born in Lynchburg in 1880, Otey was best known for her work as an economist and women’s suffrage activist. In the early 1900s, she attended R-MWC and Bryn Mawr College, where she became involved in social work. She also studied at the University of Chicago and the University of Berlin, where she earned a doctorate in economics. According to the Library of Virginia, she went on to publish reports on child labor legislation and employer welfare work for the Department of Commerce and Labor, and in the 1910s, she served as a member of the National Conference of Charities and Corrections.

In 1911, Otey helped found the Lynchburg Equal Suffrage League with her mother, Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne Lewis. She later marched in the national suffrage parade in Washington, D.C. in 1913, and went on to serve as vice president for the Virginia chapter of the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage and chair of the Sixth Congressional District for the Virginia National Woman’s Party.

After voting for the first time in 1920, Otey became a politician herself. In 1921, she sought and won the Republican nomination as superintendent of public instruction, becoming the first woman nominated by a major party for statewide office in Virginia. After losing the election, she ran for office as a socialist on two other occasions—first for the House of Delegates in 1931 and for the United States Senate in 1933.

Later in life, Otey worked for the Social Security Administration and the Foreign Economic Administration and published a book on her family’s genealogy. She died of pneumonia in Lynchburg in 1974.

Georgia Weston Morgan (Class of 1903)

Georgia Weston Morgan (Class of 1903)

Morgan was born in Campbell County in 1869 and is regarded as a beloved educator and one of Central Virginia’s most accomplished artists. She entered R-MWC in 1899 to study painting and art under the tutelage of the College’s first art professor Louise Jordan Smith. After graduating from R-MWC, Morgan continued her studies at the Académie Julian in Paris. Her work, which included primarily miniatures and landscapes, was exhibited at the Paris Salon and in galleries spanning the East Coast of the United States.

Morgan returned to Lynchburg committed to pursuing a career in painting and teaching. In 1915, she joined the art department at what is now the University of Lynchburg, where she taught studio art and art history for 30 years. She also set up a studio on Church Street, where she gave private lessons and continued her own work.

Morgan was a co-founder of the Lynchburg Civic Art League in 1932, and helped establish the city’s Federal Art Gallery in 1936. Both groups promoted arts education and exhibition for people of all socioeconomic backgrounds. She also advocated for the arts on a national level and was elected to the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors.

She passed away in 1951.

Mabel Lee Walton (Class of 1906)

Mabel Lee Walton (Class of 1906)

Credit: Sigma Sigma Sigma

Walton was born in Shenandoah County in 1884, and was known as a philanthropist and president emerita of the Sigma Sigma Sigma (Tri Sigma) national sorority. Tri Sigma was founded in 1898 at the Female Normal School in Farmville, Virginia. (now Longwood University). Walton was initiated as a charter member of the Gamma Chapter at R-MWC and served as Tri Sigma’s national president from 1913-1947. She also served as president of the Association of Education Sororities before Tri Sigma became a member of the National Panhellenic Conference in 1947.

According to a historical marker erected in her honor in Woodstock, Virginia, Walton “promoted ideals of integrity and service. Tri Sigma’s philanthropic efforts, including a campaign to eradicate polio in the 1950s, have aided hospitalized children throughout the country.” Today, Tri Sigma continues to follow her example and provides leadership training for women, grants and scholarships for students, and therapy programs for hospitalized children.

Walton’s family home in Woodstock, called the Mabel Lee Walton House, served as the national headquarters for the Tri Sigma organization for 50 years. She passed away in Woodstock in 1974.

Susie May Ames (Class of 1908)

Susie Ames (Class of 1908)

Ames was born in Accomack County in 1888, and was a renowned historian and author. She majored in English and minored in Latin at R-MWC and went on to hold several teaching jobs in Virginia as well as Maryland and Kentucky. She also taught at R-MWC from 1923-1955, and was later named professor emerita in history.

According to the Library of Virginia, Ames was one of fewer than 500 women to earn a doctorate in history during the years 1920-1940. Her dissertation, published as “Studies of the Virginia Eastern Shore in the Seventeenth Century,” was a pioneering investigation of social and economic history based on thorough analysis of the earliest county court records in the nation.

In 1954, the American Historical Association published Ames’s work, County Court Records of Accomack-Northampton, Virginia, 1632-1640, and in 1944, she was appointed to the Virginia World War II History Commission, which was charged with documenting the state’s involvement in the conflict. As part of the 350th anniversary of the Jamestown settlement, she published Reading, Writing and Arithmetic in Virginia, 1607-1699 (1957), and in 1965, she published “The Bear and the Cub”: the Site of the First English Theatrical Performance in America.

In 1943, Ames was admitted into Phi Beta Kappa, and in 1964, she was awarded a certificate of commendation from the American Association for State and Local History.

She died in Accomack County in 1969.

Mary Elizabeth Nottingham Day (Class of 1908)

Mary Elizabeth Nottingham Day (Class of 1928)

Known professionally as Elizabeth Nottingham, Day was born in 1907 and raised in Culpeper. She was a teacher and nationally recognized artist, and many of her paintings were inspired by her hometown. After graduating from R-MWC, she studied for three years at the Art Students League of New York and received two fellowships for further study in Europe.

According to the Library of Virginia, Day returned to Virginia permanently in the 1930s, when she was commissioned to paint a series of historical panels for a school in Winchester. In 1936, she became director of the Big Stone Gap Federal Art Gallery. Later that year, she served as director of the Lynchburg Federal Art Gallery, leading exhibitions, as well as classes in painting, composition, interior and costume design, and handcrafting. She was also the assistant state art supervisor of the Works Projects Administration’s extension service from 1940-1941.

According to a 2010 edition of the Amherst New Era Progress, Day painted numerous watercolors of Virginia landscapes, and those works, as well as drawings and oils, have been shown in exhibits extensively on the East Coast. Her pieces have appeared in at least 20 exhibitions at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and have been included in exhibits on several occasions at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. Others are in collections at Ford Motor Company and the General Services Administration, as well as several Virginia colleges, including Randolph, the University of Virginia, and the University of Mary Baldwin.

She and her husband, Horace Talmage Day, joined the faculty at what was then Mary Baldwin College in 1941, where they co-directed the art department for several years. She served as a board member and president of the Virginia Art Alliance and sat on the State Art Commission from 1950 until her death in 1956.

Lucille Chaffin Kent (Class of 1938)

Lucille Chaffin Kent (Class of 1938)

Credit: Blackwell Press

Kent was born in 1908 and is remembered as one of the first female flight instructors in Virginia who trained more than 2,000 future military pilots to serve in World War II. In addition, she authored a comprehensive aeronautics manual and a two-part series of books called That Our Heirs May Know.

According to the historic marker dedicated in her honor in Lynchburg, Kent began teaching meteorology, navigation, and civil air regulations at E.C. Glass High School in 1939. When the United States entered the Second World War, she was a ground school director in the Civilian Pilot Training Program in Lynchburg, which then became the War Training Service. During the war, she trained military pilots at the University of Lynchburg (then Lynchburg College), in commandeered facilities at the Miller Home for Girls, and at Preston Glenn Airport.

According to the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Kent also qualified as an instructor on the Link Trainer flight simulator, teaching pilots how to use navigational instruments. Prior to her career as a flight instructor, she attended both R-MWC and Ferrum College.

After the war ended, she worked as a Lynchburg area music teacher for many years before passing away in 1997.

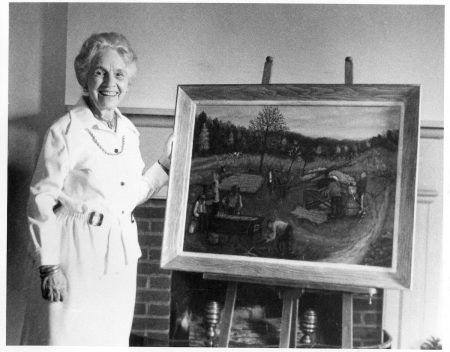

Emma Serena “Queena” Stovall (Class of 1949)

Queena Stovall (Class of 1949)

Credit: Blackwell Press

Stovall was born in Amherst County in 1887 and is known as a great American folk artist. Despite her artistic talents, she didn’t begin painting until she was already a great-grandmother. According to the Lynchburg Museum, she and her husband, a traveling salesman, were married in 1908 and had nine children. They divided their time between Lynchburg during the fall and winter and living on a farm in Amherst during the spring and summer.

In 1949, at the age of 62, Stovall’s domestic responsibilities had lessened, allowing her to take up new hobbies. That’s when her brother encouraged her to enroll in art classes at R-MWC. Stovall took a class taught by art professor Pierre Daura, who liked her natural style of painting so much that he advised her to stop taking his classes so that she could develop her own unique style without influence. Stovall and Daura formed a lifelong friendship, and he used his connections in the art world to help her rise to national fame.

Stovall was best known for her work depicting everyday events and activities in the lives of both white and black families in Amherst County. Her paintings have been featured in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA), the 1982 World’s Fair in Knoxville, Tennessee, and the American Embassy in Paris. They have also appeared in shows at the Maier Museum of Art at Randolph College, the University of Lynchburg, and the Virginia Museum of History & Culture in Richmond.

Though Stovall’s art career was somewhat brief, she is remembered among all-time great folk artists, such as Grandma Moses and Clementine Hunter. She died in 1980 at the age of 92.

Louise Jordan Smith

Louise Jordan Smith

Smith was born in 1868, served as R-MWC’s first art professor, and played a crucial role in developing the College’s art collection. A fervent believer that firsthand study of the art of one’s time was central to a liberal arts education, she devoted 35 years to the College’s art program. When R-MWC admitted its first students in 1893, she even opened her lectures to local women not enrolled at the College.

In addition to her work in the classroom, Smith established the Annual Exhibition of Contemporary Art on campus in 1911, which was believed to be the first exhibition of modern art held on a college campus anywhere in the United States. It was from this series of exhibitions—which continue to this day—that the idea of a permanent art collection grew, and the first acquisition was made in 1914 from the 4th Annual Exhibition.

Smith, who was the cousin of founder and first President William Waugh Smith, created the College’s permanent art collection in 1920, which focused on American paintings. She also ensured the continued growth of the collection with her 1928 bequest to establish an acquisition fund.

Smith studied art at the Art Student’s League in New York and at the Académie Julian and Beaux Arts (the National School of Fine Arts) in Paris. She spent a sabbatical leave in 1924 in Europe to study art in Spain, particularly at the Prado Museum. She was a member of the National Art League of America and an official of the General Federation of Woman’s Clubs.

Smith passed away in 1928, but left a lasting impression upon the College’s art program and her students.

***For more information about the Virginia Women’s Monument, visit womensmonumentcom.virginia.gov.

Tags: alumnae, magazine, Vita No. 7