Randolph students continuing virology research this summer

This story is part of an ongoing series featuring the work of faculty and students participating in Randolph’s Summer Research Program.

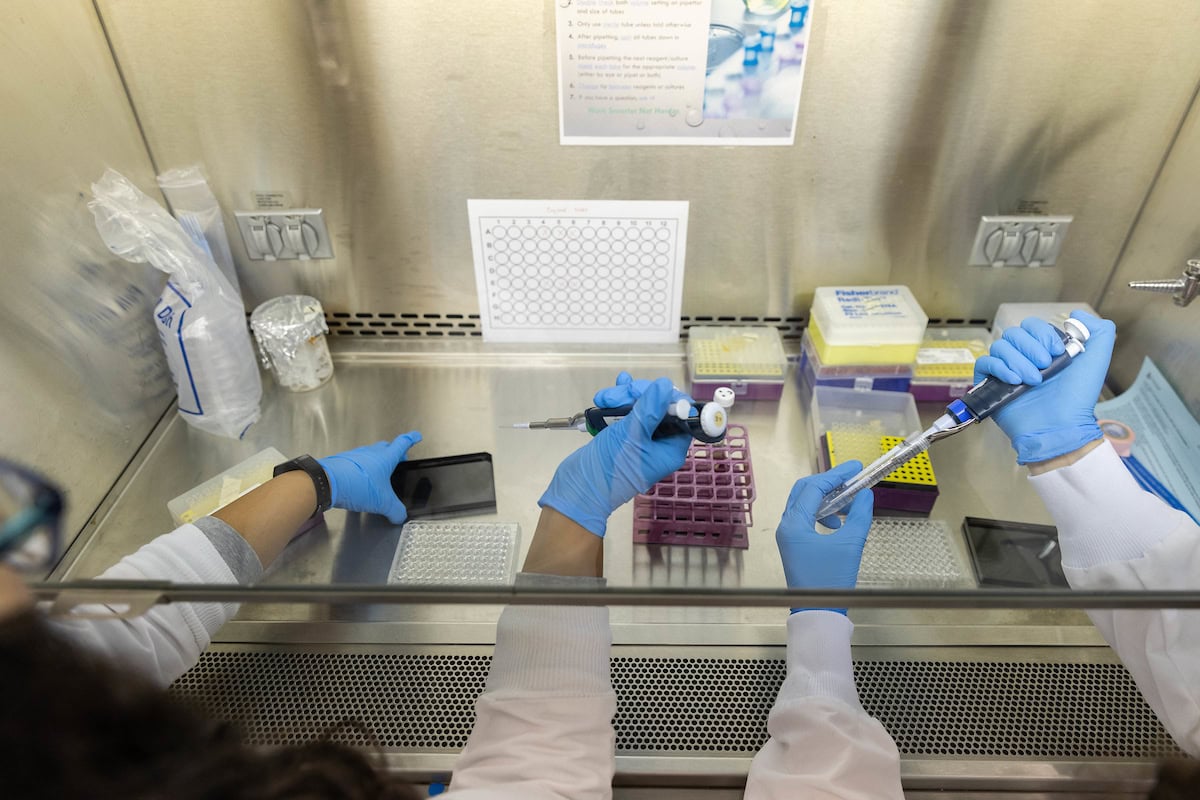

Jessica Monasir ’24, Alison Reyes Merced ’24, and professor Adam Houlihan work in the lab during Randolph’s Summer Research Program.

Alison Reyes Merced ’24 found inspiration during a virology course at Randolph last fall.

Alison Reyes Merced ’24 found inspiration during a virology course at Randolph last fall.

In the class, Reyes Merced and her fellow students worked with bacteriophages, viruses that infect and replicate only in bacterial cells.

At one point, her professor, Adam Houlihan, talked about biofilm, communities of bacteria that can grow on a variety of surfaces (examples include everything from dental plaque on your teeth to pond scum that accumulate on top of water).

“I don’t know why it stuck with me, but I started thinking about combining those two things to see if bacteriophage could be effective for treating biofilms as an alternative to antibiotics,” said Reyes Merced, a biology major. “There is a huge issue right now with antibiotic resistance.”

This summer, she’s working with Houlihan, fellow biology major Jessica Monasir ’24, and biology lab technician Sara Harper-Roche to see if bacteriophages are capable of inhibiting or disrupting Escherichia coli biofilms as part of Randolph’s Summer Research Program (SRP).

Biofilm infections, which account for many human bacterial infections, are incredibly difficult to treat.

“Where we see these infections a lot is on prosthetics,” Houlihan said. “When you introduce a non-living surface into the body, whether it’s an artificial knee or artificial heart valve, or in catheters, the bacteria stick to those nonliving surfaces. Once they form a biofilm, they’re really hard to treat. So, really, the only good remedy is to go back in and remove that prosthetic, which means another surgery.”

Using bacteriophage is not a new idea, but with antibiotic resistance becoming an increasing concern, there is renewed interest. The treatment can also be more targeted.

“It’s not going to have a collateral effect where it kills other bacteria,” Houlihan said. “Antibiotics knock out everything and affect the microbiome, whereas one of the ideas behind bacteriophage is it will really only seek out and target the susceptible species of bacteria. Sometimes, it’s not even a species. A bacteriophage might only affect certain strains of E. coli.”

This summer, they are testing two different types of treatment on the biofilm they’ve grown in the lab. One will measure the effect of bacteriophage alone in treating it, and the other will look at bacteriophage in combination with a detergent called Tween 80.

The latter treatment, if successful, could be a possible way to eliminate biofilm that accumulates in pipes.

“We are going to see which bacteriophage concentrations are best,” Monasir said. “What we hope to see is, once we incorporate the bacteriophage, the biofilm formation is less, or close to none.

They spent the entire first week of SRP writing up the protocols they’ve been using, leading to a smooth transition to their lab work.

“They’ve been extremely productive, and they’ve already gotten a lot of really useful data,” Houlihan said. “It’s nice because it’s their project. They’re the ones perfecting all the protocols. They’re also learning that, when you do quote-unquote real science, things rarely go how you think they’re going to go. It’s a good experience.”

Tags: biology, summer research 2023, Summer Research Program