The beginnings of the College: R-MWC in the 1890s

Front campus of R-MWC in the 1890s

Randolph College was founded as Randolph-Macon Woman’s College in 1891, and officially opened its doors to students in 1893. The following article was written by Meta Glass (Class of 1899) in the fall of 1965 about her experiences as one of the first students enrolled at R-MWC in the 1890s:

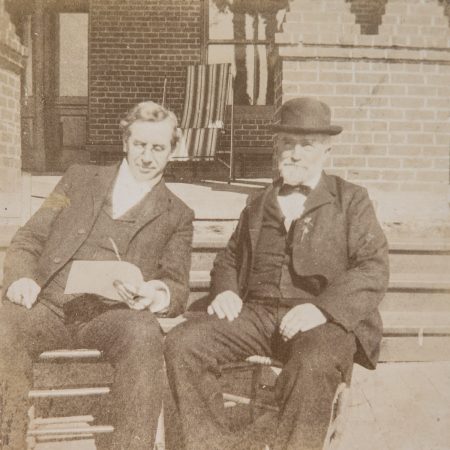

One cannot tell how long a dream may be forming consciously and subconsciously, but when 1891 came Randolph-Macon Woman’s College was still a dream. Land had been acquired and plans drawn, but the red clay stretch had no buildings, no trees, no walks, only a dynamo of devoted and intelligent determination producing the power that by September 1893 produced the College. Of course this dynamo was William Waugh Smith, and one can no more talk about Randolph-Macon in the nineties without talking about him than record the settling of Kentucky without sketching Daniel Boone.

Meta Glass (Class of 1899)

He wanted in Virginia a college for women that would give them the educational opportunities that Virginia men had long enjoyed, not an educational institution, however good in its way, that viewed the educational needs of women on a restricted and softened basis. Dr. Smith wanted the minds of women fed and stretched to produce better rounded human beings than such a regimen could afford. A woman ought to be, in his mind, all that she had ever been and more besides, and his Woman’s College was to foster “the more besides.”

He had been able to interpret his dream to others in convincing enough form to secure understanding, sympathy, money, land, and even “gift bricks,” and he was gathering together the people who could make the dream come true.

In September 1893 Main Hall from the front door east was built. It housed everybody and everything. The president’s office, the business office, the package room, the telephone—one only!—and a storage room were all where is now the east half of the lobby, and the west half of the lobby was the “parlor,” with painted walls and yellow oak woodwork and furniture which could just be called furniture. There are no adjectives appropriate to it. Many men still in Lynchburg can recall this room, the only place for visitors to be chaperoned first and entertained second, in full view, through a clear glass transom, of strings of girls along the stairs. Courting actually was done there, as many marriage registers can prove.

The chemistry laboratory was on the left as one enters the dining room, and classrooms ran along the main hall, and the library was where the registrar’s office now is. In that era of golden oak, inevitably the bedrooms were so furnished, and an acetylene gas plant in the basement of Main Hall furnished the lights.

There was no need of a dean’s office nor a registrar’s office, because there was neither dean nor registrar. Students entered college through the president’s office, were registered there, one by one, at a roll-top desk, by the president himself and guided throughout their college years by the president and faculty, a cooperating group without differentiating titles.

The psychology laboratory in the 1890s

A student’s reaction to the mention of mathematics and Latin was the barometer of intellectual ability and curiosity, but her course was by no means limited to these studies. Sciences, languages, mathematics, psychology, and philosophy all students took, and by 1896 they took history also.

The grounds were enclosed by the wire fence over which in the next few years honeysuckle made a hedge, good to look upon and ravishing in its fragrance on early summer nights. There was only a wooden gate in the hedge, a necessary interruption of the flow of green and blossoms. The front walk was laid out and the maples were planted and so was the wisteria. An early excitement was the two miles of graveled walks through the pines and grounds.

Rivermont Avenue was just called “the road.” It was unpaved, with the street-car tracks lifted in the center on a kind of wooden trestle, from which stepping-stones, three feet high, helped one to the college entrance. The pines were thick and unbroken by houses. The mountains were as blue and lovely as today and no houses occupied the foreground of the view. The street-cars made it from Main Street in about twenty minutes and everybody used the street-cars.

By the fall of 1897 Main had been extended to the curly stairs on the west end, and the imposing library with a narrow gallery running all the way around the second story occupied the space that is now the Senior Parlor. In 1899 the west wing of Main was built and that brings Randolph-Macon to the twentieth century.

Far more important than the building and the grounds were the persons who gathered there during the seven years of the 1890’s after the opening. Besides Dr. Smith, there was Dr. Martin, whom the present students know as the chemist for whom the science building was named, but whom the old students knew as an inspiring, exacting, sarcastic, jovial man. He was a strong teacher in his field, as strong for order and discipline in his laboratory as is nature in her laws. When students called on Sunday nights he was jolly and entertaining and teasing with always a way of piquing one’s intellectual curiosity. On that morning he had conducted a Sunday School class in the laboratory marked by both hard thinking and spiritual aspiration on the part of the whole group. His chapel services always had a quality a little different from those of anyone else. They were so pregnant that they kept developing in the mind afterwards. He was a large man with large fingers and he rolled as he walked. Had not his mind glowed so perceptibly, the emotion in the minds of students meeting him might have been not unlike the respect and affection that greets a Saint Bernard.

Original faculty for R-MWC

Mr. Sharp was no less determined a man than Dr. Martin, but all the outward aspects of his strength were different. He was soft-voiced, small, extremely shy outwardly, concerned that his students should know the best—and only the best. A copy of Horace read in his classes would be marked copiously with “Omit…to here.” Horace, the delicious scalawag, was not the Horace he taught. Ah no—his Horace was urbane, graceful, moral and uplifting only. The jokes of Terence were his kind of jokes and Seneca’s wisdom and Vergil’s harmonies were alive not only to him but in him.

Mathematics, psychology, logic and ethics, and the history and practice of education all were in the hands of Miss Parrish. She had a noble forehead which she rubbed upward unconsciously when engaged in deep thought and quick exposition, and the ideas glowed as Aladdin’s lamp glowed from rubbing. It was not, however, the forehead that any young girl would long for as she studied her possibilities in the mirror. Miss Parrish was tall, had a waist measuring thirty-six inches when the prevailing style was an eighteen, and her features spoke of strength and inspiration rather than of beauty. And yet the young knew that in a company of women all others palled when she entered the room. She always overworked her students, but then she had always overworked herself, and she would not reflect upon their dignity and ability by expecting less of them. Perhaps at no time would she have been a man’s woman. Certainly she was not a man’s woman in the gay nineties. Men found her difficult to deal with because they could only conceive of her as a lady and she conceived herself as a human being, and in her keen interests she went too directly to the point for their conception of her.

William Waugh Smith, founder and first president of R-MWC (left) on the steps of Main Hall

All the teachers of those early days cannot be sketched in this article. Two others stood out in the experience of the students of the nineties to such an extent that they cannot be omitted. There was Mrs. Saunders, teaching French and German, and Mr. Armstrong, teaching English. Mrs. Saunders the girls always thought of as cultured, a bit vague and indirect, much concerned with their improvement, but living on a sophisticated level to which they might expect to be admitted only here and there for a little while. One read in her classes, though, a vast amount of literature and there was no telling to what level it might raise one in the end.

Mr. Armstrong was as methodical and precise as Mrs. Saunders was indirect. His teaching was no coddling. He found the weakest point, brought it into full view, and kept your attention focused on it until in very self-defense improvement was salvation.

The faculty wives were also a distinct part of a Randolph-Macon education. Mrs. Smith with her beauty, Mrs. Sharp with her wit, Mrs. Martin with her friendliness, set tones in the daily life, and Mrs. Blackwell was incarnate love and common sense and beauty and determination, the full force of which all girls felt. The students themselves were, in those first seven years, mostly girls from the various southern states, rather homogeneous in background, more than a little self-conscious in going to college at all when, perhaps, only two or three out of any local group went to college. They considered Randolph-Macon a wonderful experience and believed that if it had not existed they would have missed the experience altogether. They were no more able and not much more studious than any other college group then or now, but they did recognize that they were privileged and that they carried in their lives the reputation and the prestige of a young college, for which they were vastly ambitious.

How did they live and work together in this small closely-knit group? They went to class and kept quiet—really quiet—hours and worked in the library and the laboratory, treading the paths of all study, and they discussed the world and civilization together and easily with the older members of the community. Students sat at tables in the dining room with a faculty member or a couple, often all four years at the same table, and got a family feeling.

The first graduating class at R-MWC

There were no sororities, a few small clubs, and two competing literary societies, which had literary programs but were also centers of intense loyalty. One was named for Washington and one for Franklin, immediately shortened to Wash and Frank, and a girl was either an unspeakable Wash or a Grand Frank, or vice versa according to the person speaking. The wit who pinned a placard saying “Wash Hall” on the bathroom door had unlawful interest on her cleverness from the Franks for year after year. The Am Sams, and just afterwards, the S.T.A.B.s were founded, by the skin of their teeth, in the nineties.

There was no store nearer than Lynchburg, no tea room, no book shop. Bell’s was at the other end of the phone line as was one especially favored grocery store, and purchases came out on the street car and were received into the hands of the purchaser waiting on the stepping stones to keep the package from the mud or the dust. What the students ate from these orders, however, was just what college girls eat, and seem to have eaten since colleges were founded.

In the nineties Randolph-Macon girls did not play cards or dance, except under penalty if they were discovered so occupied. Nor did they give plays, and certainly they did not wear trousers, except the good old bloomers for basketball that took five yards for a pair and appeared nowhere but on the basketball court or the gym floor. Music flourished and concerts were greatly enjoyed and scenes from classic novels gave scope for getting out of one’s character. Parties were friendly and simple, but there was too much eating, because that was the easiest form of entertainment when elaborate preparations had not been made. Dates were then “beaux” to the girls, and “callers” to the elders, and they came with full preparation, on stated occasions, and talked often with a box of candy for lubricant.

It is too easy to call this life restricted and dull and to wonder whether it ever stirred intellectual zest when it is compared with the richness of present day offerings. But it distinctly was not dull and it did call out great zest for opening doors into unknown fields of knowledge and for the cultivation of human relationships with leisure and thoroughness. There is nothing like a dash of asceticism to deepen the appreciation of what is at hand, and people, real people, and the riches of the ages in books were at hand, and the students of the nineties were truly privileged and knew it and were happy in their life.

A student on front campus in the 1890s