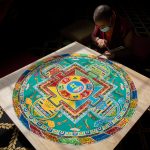

Sands of time: Grain by grain, visiting lamas painstakingly create special mandala on campus

Lamas work on the mandala in the library this fall.

The paintbrush moved swiftly, drawing a line in the sand as the intricate, brightly colored design below it faded away.

The dissolution of a sand mandala offers a marked contrast to its creation, when colored sand is applied, grain by grain, in a painstaking process that can last anywhere from days to weeks.

The Randolph community witnessed that process this fall, when three Tibetan lamas spent a week building one inside Lipscomb Library.

In Tibetan Buddhism, mandalas are geometric representations of an abode of a particular Buddha, created to serve as a center for intensive meditation after their completion.

The one at Randolph was done for educational purposes, and the opening and closing ceremonies, as well as the lamas’ daily work, were open to the public.

“I thought it would be a wonderful way to kick off the new year, when everyone was allowed to be together on campus again,” said comparative philosophy professor Suzanne Bessenger.

This is the third mandala created at Randolph, following ones in 2011 and 2013.

This time around, Bessenger approached Hun Lye, a spiritual leader in the Drikung Kagyü lineage of Tibetan Buddhism and a friend of 20 years, about visiting the College.

The mandala he chose for Randolph has a rare configuration, featuring the Buddhist goddess Vasudhara and her four male attendants. Typically, a design will feature a male at the center, with male or female attendants, or a female deity surrounded by females.

The significance of the arrangement wasn’t lost on Bessenger or Lye.

“I thought it would be kind of nice with the history, the core, of where this place came from,” he said. “It was centered around women, and now it’s expanding out.”

Building bridges

Lamas are spiritual leaders authorized to teach Buddhism, but who don’t take the extensive vows monks do, which limits what they can do in day-to-day life.

Lye is the founder and spiritual director of Urban Dharma, a Buddhist temple in Asheville, North Carolina. He was joined at Randolph by Konchok Sonam Karushar and Nima Gylan Tamang, who lead centers in Boston and Philadelphia, respectively.

Bessenger invited them to campus to coincide with the lecture, “Buddhism, Meditation, and Cognitive Science,” which is offered to all first-years in their Life More Abundant seminar.

She and psychology professor Blair Gross co-taught the lecture, which looked at not only the physical and religious foundations of meditation but also the science behind it.

“I am a really big proponent of intercultural learning,” said Bessenger. “We can’t travel right now, but we can bring a little bit of this world to our students.”

For much of his life, Lye has straddled two worlds.

Hun Lye speaks during the mandala’s opening ceremony.

Raised in a Buddhist household in Malaysia, he studied and practiced Buddhism with teachers of various traditions from a young age. He came to the United States in 1989 to attend college and met his first Drikung Kagyü teacher, which led him to his primary lineage identity.

In 2003, Lye earned his doctorate in religious studies, specializing in Buddhism, from the University of Virginia. This is also where he met Bessenger.

He spent the next 10 years teaching religious studies at two universities while leading a small Buddhist community in Asheville. Lye founded Urban Dharma in 2011, and left academia two years later to devote himself to it full time.

“When you teach a non-mainstream religion, you do it in a secular, academic context. You are building a bridge, hoping to facilitate an understanding and appreciation among people who did not grow up with it,” he said. “At some point, I decided I would be more effective bridging the other side, taking fresh academic insights on Buddhism to the Buddhist world.”

Those dual residencies, as Bessenger called them, made him the perfect choice to lead the mandala’s creation and engage with the community about it. During his time at Randolph, Lye held two public teachings and gave a lecture focusing on various aspects of Buddhism.

“He has this cultural insider knowledge that is interesting to two different audiences and shows two different perspectives,” Bessenger said.

When they began discussing his visit, she asked Lye to incorporate the idea of abundance into the mandala—something he reflected on during the opening ceremony.

“When we talk about abundance, it’s not necessarily prosperity,” he said. “It’s about not letting our hearts shut down. When your heart is open, your mind is open. When we have clarity of mind and purpose, we can find our place in this world and know how to be good to ourselves and others.”

That message resonated with September Taylor, who is taking a creative writing class at Randolph with plans to transfer to the College next year. She stopped by the library every day and attended Lye’s public teachings.

“It was one of those moments that reminded you to pay attention to what makes you happy,” she said. “It was something I really needed to hear.”

Tools of the trade

Cups of brightly colored sand sat on the floor, surrounding the trio as they worked.

Lye, Karushar, and Tamang moved around the design methodically, using a traditional tool called a chak-pur, a ridge-lined funnel that comes to a fine point at one end. Sand is scooped into the chak-pur’s wider end, and the ridges are scraped with a stick to move it onto the mandala.

Each took on tasks that needed to be done or fit their particular skill set. Certain aspects of the design are fixed, Lye said, but others can be more organic.

The mandala’s creation was an abbreviated version of what would occur in Asia or at the Buddhist temples Lye, Karushar, and Tamang lead.

There, a mandala’s creation is part of a larger ritual.

“In the West, the crescendo is the completion and destruction of the mandala,” said Lye, likening it to building a house, then immediately knocking it down. “In Asia, nobody comes to watch the mandala’s creation. It would be like watching someone set up a tent for a party.”

The meditations and rituals surrounding the completed mandala can last for days or even weeks before it is ultimately dissolved. Or, as Lye put it, when “we don’t need the tent anymore.”

The first hour or two are the most crucial in the construction of a sand mandala, as its creators lay down the grid that will eventually be filled with colored sand.

“After that,” Lye said, “it’s just a lot of patience and paying attention.”

Lye said they don’t intentionally meditate while creating the mandala. But “without a choice, your mind is meditating,” he said. “To get the task done, you have to be present.”

Sand mandalas are fragile, but ultimately forgiving—a process that can provide a lot of lessons, Lye said, if you’re paying attention.

“To paint with sand is not easy, but to correct mistakes is,” he said. “Think about how that applies to life. The mandala shows us the ephemeral nature of life. It’s fragile but wrongs that have been done can be corrected as long as we don’t get stuck.”

Their week at Randolph concluded with a closing ceremony at the library.

Attendees circled the completed mandala before Bessenger and Karushar began the dissolution, swiping the paintbrushes through the sand.

Children were invited to help, each taking a turn with the brush.

Some of the gathered sand was handed out to guests, and the rest was poured into a tributary near the College, another aspect of the ritual.

“The sands are considered blessed,” Bessenger said. “The sand goes into a tributary that leads eventually to the ocean so the blessings can spread over the whole world.”

Tags: mandala, sand mandala, Vita No. 11

Tags: mandala, sand mandala, Vita No. 11