Students analyzing mouse calls, and training a network to detect them, for summer research project

This story is part of an ongoing series featuring the work of faculty and students participating in Randolph’s Summer Research Program.

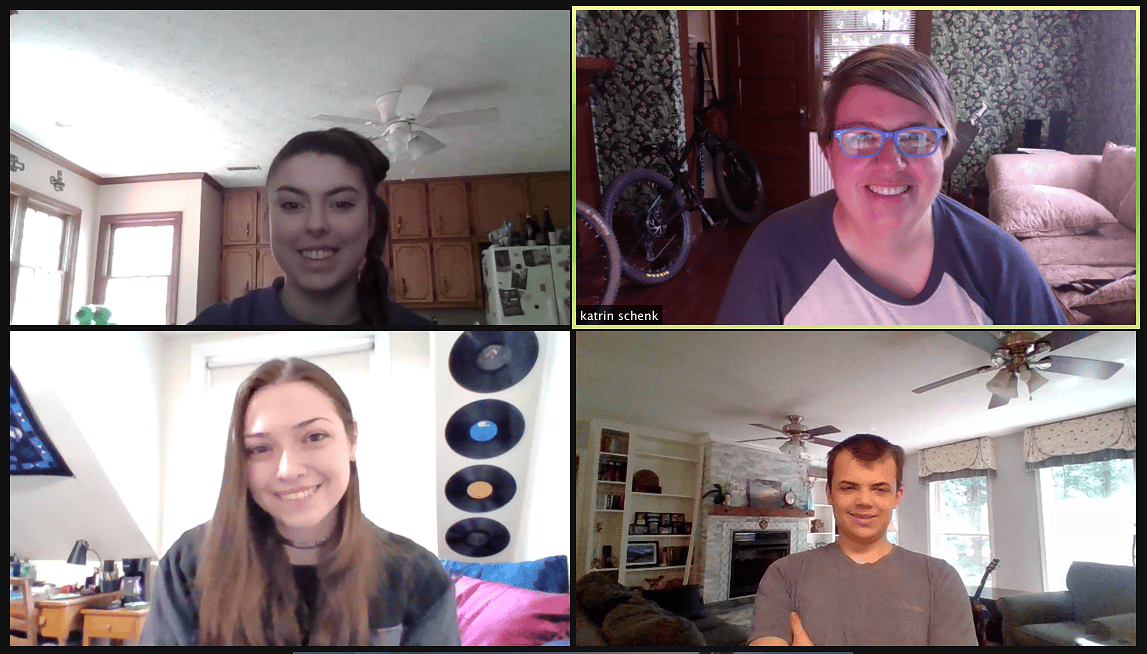

(Clockwise from top left) Kylee Bennett ’24, professor Katrin Schenk, University of Alabama student Sam Owen, and Mikayla Jenkins ’23 are collaborating on a project for Randolph’s Summer Research Program.

Last summer, Randolph professor Katrin Schenk and a group of students worked to evaluate a program called DeepSqueak, which is used to detect and classify mouse vocalizations, for the College’s Summer Research Program.

Now, Schenk is working alongside a different group of students to build a new network that will outperform it.

Developed in 2019, DeepSqueak takes audio recordings of mouse vocalizations, or calls, that can’t be heard by the human ear and turns them into sonogram images.

“We started looking at segments of noise files the other day,” said Kylee Bennett ’24. “You can adjust the color of the picture, basically, and what it does is show you the soundbite. It’s easier to see if it’s an actual mouse vocalization or if the sound is the mouse hitting the side of the box or something from the environment they were in.”

Bennett is working virtually alongside Schenk, Mikayla Jenkins ’23, and University of Alabama student Sam Owen, who lives in the area and has extensive programming experience.

“The first goal is just to train the network with more data because we have a lot more data than they used to train the network originally,” Schenk said. “And our data is probably a bit more varied as well because we have a lot of different paradigms it was taken under.”

Bennett and Jenkins are verifying sound data collected by Schenk and her collaborators over the past 10 years, including some data that was evaluated last summer. The files come from colleges and universities all over the country, totalling more than four terabytes of sound data.

Those verified vocalizations will then be used by Owen and Jenkins to build the new network.

“They’re making sure what’s being called a mouse call is really a mouse call. Or maybe some mouse calls were missed,” Schenk said. “It’s basically like writing it down, but they use the code to write it down and make sure there’s good data going in.”

Mice use the vocalizations in social situations, making them a good proxy for human social behavior and communication. That, in turn, can offer a unique insight into diseases that affect communication and social behavior, using mouse models of those diseases to test treatments.

That was one of the reasons why Jenkins signed up to work on the project.

“I’m a physics and engineering student, but through my entire life, I have always been interested in broad sciences like biology and psychology,” she said. “We are working with programming for applications that can be used in medicine, biology, and psychology. It ticked all of the boxes of things I’m interested in. I also think, where I want to go in the future with engineering, I could really benefit from the programming experience.”

Tags: Katrin Schenk, research, student faculty research, student research, summer research, summer research 2021, ultras