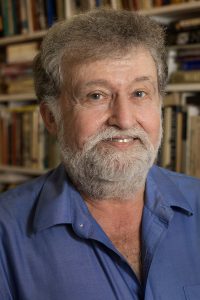

Retiring history professor John d’Entremont reflects on four decades behind the Red Brick Wall

This story is part of a series featuring faculty members who are retiring in 2021.

John d’Entremont

John d’Entremont, Randolph College’s Theodore H. Jack Professor of History, originally planned to be a journalist.

After graduating from the University of Virginia in 1972, he went to work as a typist for United Press International. Yearning for more action, he eventually left to join the state campaign staff for George McGovern’s presidential run.

He loved the work, though it was exhausting and left him drained at the end of each day. But he’d always find time to read from one of his history books before drifting off to sleep.

“I’d liked history for a long time, had majored in it in college, and was convinced of its value,” he said. “But those late night time hours during the campaign deepened my regard and affection for it. The campaign was all action, with little time for extended reflection and meditation. But the historians I was reading had time to ponder, to think, to fully assess their evidence and refine their conclusions.”

“I envied that,” he added. “I envied them.”

So d’Entremont began applying to graduate schools—he earned his Ph.D. at Johns Hopkins University—and the rest, as they say, is history.

He joined the faculty at Randolph in 1980 and is retiring this year. Here’s more of what he had to say about his time here.

Where did your passion for history come from?

“My intense interest in history, I suppose, emerged partly from being an Army kid and living in several parts of the country before I turned 12. I couldn’t help but notice what a complicated, diverse, perplexing, mysterious, and fascinating country this is. My father was stationed at Fort Monroe when I was 11, during the hoopla in Virginia over the Civil War Centennial. I got a gigantic history of the Civil War as a Christmas present and stayed up through several consecutive nights devouring it. I was stunned that just a 100 years earlier people from Virginia and Massachusetts, where my parents were from and most relatives lived, were consumed with trying to kill each other. I wanted to know why. And I’ve been asking why, in response to all sorts of puzzlements, ever since. I haven’t solved all the riddles, but I have found that history is always an essential part of the explanation for any social, cultural, and/or political problem.”

What is your teaching philosophy and how have you approached that here at Randolph?

“Nothing fancy. Be yourself; you can’t be anyone else convincingly. Believe in the importance of what you’re teaching, and make sure you like teaching it. If you can’t do either or both of those things, your students will sense it in the first five minutes, and you really should find another line of work. Respect your students. Correct your mistakes; never pretend you know everything. Take your subject more seriously than yourself, and make room for humor.

“When it comes to teaching history specifically, try to get students to understand that they are linked with past people—and what we do will link us with future people, who will be born long after we are gone. The Great Casting Director has cast us, past people, and future people in different parts of the drama, but it’s all the same play. And to play our parts well, it’s helpful to know what’s happened in the play before our own moments upon the stage.”

What are your favorite classes to teach?

“The subject doesn’t matter. Without doubt, my favorite classes are those in which at least most students are interested and engaged; who understand that learning and fun are companions, not polar opposites; who contribute in some way to the class; and who actually do the work. When that happens in a classroom, there’s almost nothing that can beat it.”

Over the years, you’ve had several resident and research fellowships. What, if any, impact did they have on your work with students and in the classroom?

“The opportunity to do research and to travel, whether in Virginia, elsewhere in the U.S., or in distant parts of the world, has been absolutely crucial to enriching my life and, I hope, my teaching. You can’t teach what you don’t know, and time away from the classroom getting to know people living and dead, as well as exploring places far from your own comfort zone, can’t help but give a person a needed sense of finiteness and humility, as well as gratitude for the chance to plug in to other people’s wisdom and experience, and to look at one’s own country, culture, or subgroup from a different angle of vision, seeing it all in new ways.”

Can you tell me more about your research interests?

“I’ve always been most interested in reform and social change. I want to know what causes change and what prevents it; whether individuals can bring about great change, and if so, under what circumstances. I am most drawn to reformers and radicals in the past, especially in the 19thcentury and early 20th. I have spent so much time with 19th-century antislavery radicals that I feel that I know many of them better than I know the living people in my life.”

What advice would you give students?

“Repeat after me: There’s no such thing as too much knowledge. Repeat after me: There’s definitely such a thing as too little knowledge. Live a life grounded in knowledge, reason, and kindness, and you’ll probably be OK. Beyond that, spend this precious time of your life figuring yourself out. Who are you, as a truly independent person, not someone solely devoted to meeting other people’s expectations? What do you believe? More importantly, what do you believe in? Once you think you’ve figured yourself out—at least for now—be brave and bold enough to actually be yourself. And finally: Beware of people who presume to offer you advice.”