Remembering the Patterson Six: A decision to make a stand for civil rights earned two R-MWC students jail time—and a spot in history

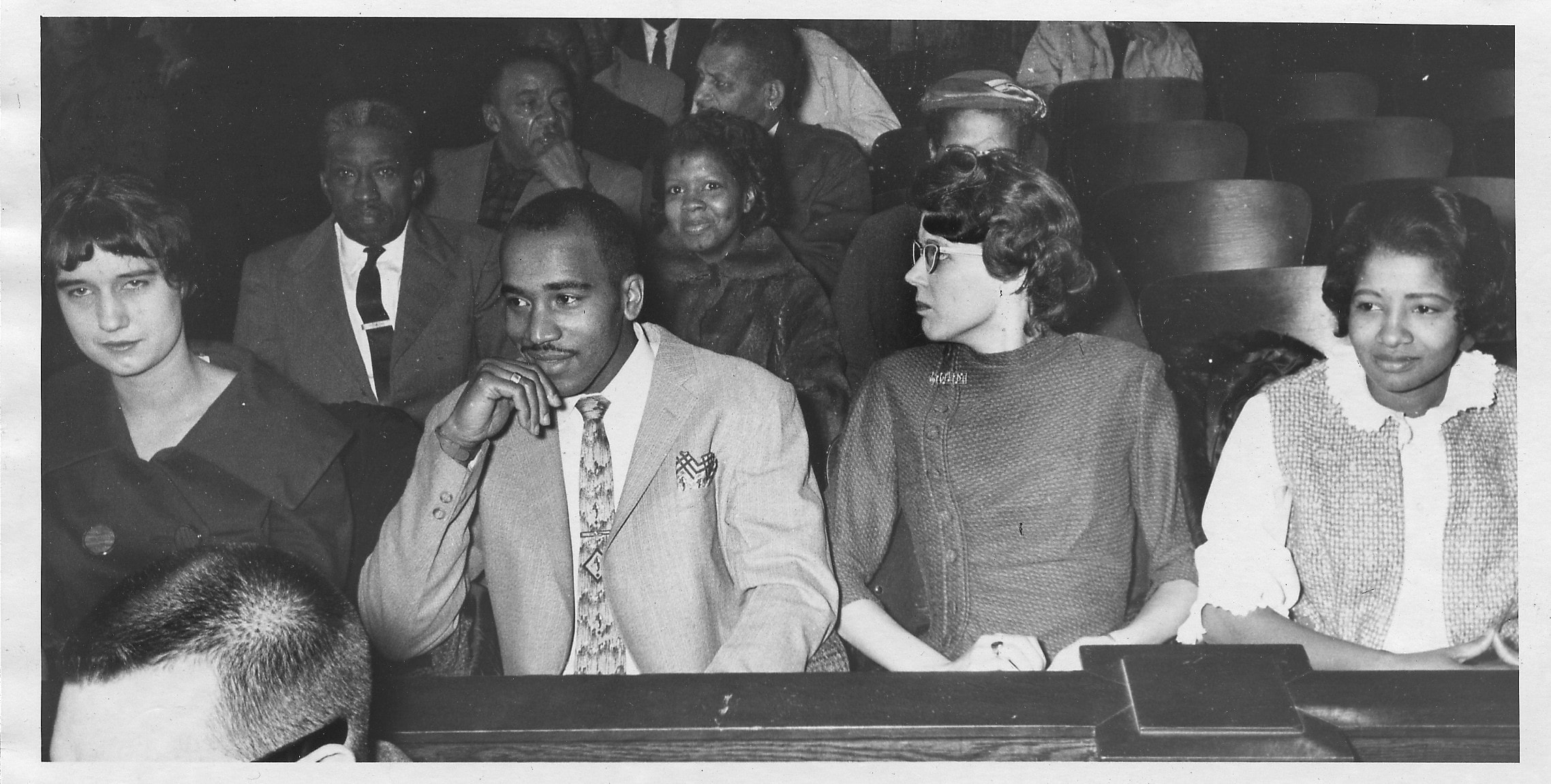

(Left to right) Rebecca Mays Owen ’61, Kenneth Green, Mary Edith Bentley Abu-Saba ’61, and Barbara Thomas joined two other members of the Patterson Six in court, where they would be sentenced to 30 days in jail for holding the city’s first civil rights sit-in. Photos of the protest and court proceedings were printed in “The News” and are reprinted with permission.

Editor’s Note: This year marks the 60th anniversary of Lynchburg’s first civil rights sit-in. Two of the College’s students were members of the Patterson Six, as they came to be called, and were ultimately jailed for their actions. The following story about that defining moment in Lynchburg’s history was first published by Randolph College in the fall of 2010. Rebecca Mays Owen ’61, one of the Patterson Six, passed away in 2002, and William Quillian, Jr., then-president of R-MWC, died in 2014. Mary Edith Bentley Abu-Saba ’61 also passed away in October 2020.

On December 14, 1960, four white and two African American college students—including Randolph-Macon Woman’s College students Mary Edith Bentley Abu-Saba ’61 and Rebecca Mays Owen ’61—entered a Lynchburg drugstore hoping to convince the owner to let them have coffee together.

The result—the city’s first sit-in—landed the college students in jail, prompted additional sit-ins from classmates, and ignited a firestorm of controversy throughout the city, all the while teaching the R-MWC students involved a few important lessons about life, social justice, and courage.

‘I told her I’d go if she promised we’d be back by dinnertime’

Mary Edith Bentley Abu-Saba ’61 had just finished eating lunch on December 14, 1960, when her good friend Rebecca Mays Owen ’61 asked for a favor. They were both members—along with about a dozen of their classmates—in a local group affiliated with the YWCA. Consisting of African American and white students from local colleges and the community, the group met frequently—much to the chagrin of local alumnae and community members—to talk about college, life, and racial relations.

(Left to right) Kenneth Green, Mary Edith Bentley Abu-Saba ’61, and James Hunter are photographed by the press shortly before being arrested during a sit-in at Patterson Drug Store.

Some of those students planned to visit a local lunch counter that evening in hopes of persuading the owner to serve African Americans. Owen wanted Abu-Saba to go. “I told her I was on my way right that second to Presser Hall to practice for my music lesson the next day,” Abu-Saba said. “I told her I’d go if she promised we’d be back by dinnertime.”

Abu-Saba never made the rehearsal session. That split-second decision changed both of their lives and carved a prominent spot for the young students in Lynchburg’s civil rights history.

‘We weren’t out to make history’

On that afternoon just before winter break, Owen and Abu-Saba joined Lynchburg College students James Hunter and Terrill Brumback and Virginia Theological Seminary and College students Barbara Thomas and Kenneth Green at the doors of Patterson’s Drug Store in downtown Lynchburg.

Later dubbed the Patterson Six, the four white and two African American students did not plan to hold a sit-in, though they had heard about a few others that had been held in Greensboro, North Carolina,

and other larger cities. What they really wanted was to talk with William S. Patterson, the owner of the drug store, and explain why he should change his lunch counter rules. Lunch counters in four other downtown stores had been integrated during the previous month, and the students wanted to see the remaining stores follow suit.

“We didn’t have a big plan,” said Abu-Saba, who went on to become a psychologist and outreach director for a California-based nonprofit organization that rebuilds Palestinian homes and schools. “We weren’t out to make history. We just wanted him to come around to our way of thinking. I think we really believed he would just change his mind after we talked to him.”

Patterson Drug Store, which was located in downtown Lynchburg, was the site of the city’s first civil rights sit-in.

The students entered the store and asked to speak to Mr. Patterson. When he refused to come out, they reconvened outside.

“We stood out there on the corner and talked about it,” Abu-Saba remembered. “And then we went back in and sat down and asked for coffee.”

It was something Owen and Abu-Saba had done many times during their college years. This time, however, was different. The waitress started pouring coffee and then froze when she saw the African American students. Soon after, a red-faced Mr. Patterson stormed out to the lunch counter and demanded the students leave.

‘Just stand up and walk out’

“Nobody said a word. We all just looked at each other,” said Abu-Saba, the daughter of a Methodist minister. “He said he’d call the police. And we just looked at each other again, and nobody got up. I was scared, but I was feeling stubborn. I felt connected with the spiritual, mental thing inside you that says ‘I’m going to try and do the right thing.’”

The police arrived, and an officer gave the students one more chance. “You can end this right now,” he reportedly told the students. “Just stand up and walk out.”

Abu-Saba remembers telling herself she was not going to move and catching the same sentiment in the eyes of her friends. “We all just stubbornly sat there,” she added with a soft chuckle. “And the rest is history because of our stubbornness.”

Newspaper reporters and photographers arrived at the lunch counter shortly after the police and snapped photographs of the students as they were arrested on trespassing charges. “My mom later saw the newspaper photograph with my chin jutted out and said, ‘I know that look. That’s your stubborn look,’” Abu-Saba said.

Barbara Thomas, left, and Rebecca Mays Owen ’61 are arrested during a sit-in at a lunch counter in Lynchburg that refused to integrate in 1960.

A patrol wagon pulled up and took the students to jail, where they “arrived too late for supper,” according to a story in the December 15 edition of The News, one of Lynchburg’s daily newspapers. The police separated the students by gender and race in the jail. Owen and Abu-Saba sat quietly in the cell together, unsure of what would happen next.

Owen called her good friend Alice Hilseweck Ball ’61, who was also a member of the YWCA student group.

“Mary Edith told me I needed to call somebody to help get them out,” Ball remembered. “I don’t think they really thought they were going to end up in jail that day, but they did. They picked the toughest drugstore.”

Phone calls began circulating around campus, and Mary Frances Thelen, the girls’ religion professor, called R-MWC President William Quillian, Jr. at home to break the news. Quillian remembers calling A. Montague White, the College’s business manager, and the pair went down to the jail to post the $1,000 bond for each of the R-MWC students. In total, the students spent about three hours in jail that evening.

It was a night neither they nor Quillian would ever forget. “It was the only time I ever had to go bail out students from jail,” he laughingly remembered. “That never happened again, I’m happy to say.”

‘…You wondered if this was the right way to go about it’

Quillian knew a group of R-MWC students had been meeting for months around town with African American students and members of the community, and he supported their efforts, though many in the R-MWC community did not. Even before the sit-in, he received a visit at home from 12 local alumnae who vehemently opposed those meetings.

“They thought this business of R-MWC students meeting with Black community members must stop. They did not think it was proper. I think they were surprised when I told them I thought it was a good thing,” Quillian commented.

The student sit-in, however, brought mixed emotions.

“You believed in what they were standing for, but you wondered if this was the right way to go about it,” he said.

Quillian and many others in the city had been working behind the scenes trying to convince businesses to desegregate. They were slowly making progress.

“That’s why many of us had mixed feelings about the sit-in,” Quillian said. “There were members of that commission who felt the sit-in was counterproductive and would set back the progress we had made.”

The fallout

The local newspapers, known for their opposition to integration, printed large photographs and articles about the Patterson Six protest the next day.

(Left to right) Mary Edith Bentley Abu-Saba ’61, James Hunter, Barbara Thomas, and Rebecca Mays Owen ’61 wait outside the courthouse before their trial in January 1961.

Many alumnae were outraged, and members of the community accused R-MWC’s president and faculty members of instigating the sit-in. Members of the interracial commission distanced themselves from the students’ protest, while others in the community applauded their courage. On R-MWC’s campus, the reaction was mixed.

Joy Mitchell Price ’61 remembers how news of the sit-ins enveloped campus. “I was so proud of them,” said Price, who was also a member of the YWCA race relations group.

She later went on to become a writer and created a nonprofit agency in Maryland that provides mental health programs and services, including a rape crisis center.

“No one knew they were going to do the sit-in, but I remember thinking I needed to be as supportive of them as I could,” Price said. “Most people had nothing to say, and a lot of people only talked to their close friends. The atmosphere was pretty tense at times and some really chastised them.”

“The fact that members of my class had taken this step just made me proud of them.” she added. “I have always felt glad to have been there when it happened.”

Abu-Saba remembers friends who refused to speak to her, and her music professor sat her down for a long talk. “He told me he applauded me, but at the same time, he was scared for me,” she said.

In the newspaper accounts, the students vehemently denied rumors their professors put them up to the sit-in. Quillian faced mounting pressure to expel the girls. Several trustees demanded he take the matter to the Board of Trustees; he refused on grounds that it was an administrative matter.

The day after

Emotions ran high the day after the sit-in as R-MWC prepared to close for the holidays. That evening, Owen and Abu-Saba were brought before the Judiciary Committee where they learned they would not be expelled. They did endure “stern” disapproval from the College administration for breaking the law and had to promise not to be involved in more protests.

Even as the Judiciary Committee was meeting to decide the fate of Owen and Abu-Saba, Ball, Jane Meredith Wolf ’61, Lynda Blackwood ’62, and Virginia Shearer Renick ’62 joined Miriam Gaines, an African American student from a local high school, at People’s Drug Store downtown.

“It seemed that it was very important for there to be a second sit-in quickly,” said Ball, “so it didn’t look like the first was an isolated incident. We needed them to know that there were other people who felt the same way. Patterson’s wasn’t the only one being discriminatory.”

(Left to right) Miriam Gaines, a local high school student, joined Jane Meredith Wolf ’61, Virginia Shearer Renick ’62, Alice Hilseweck Ball ’61, and Lynda Blackwood ’62, for a sit-in protest at People’s Drug Store shortly after the arrest of the Patterson Six.

According to newspaper accounts of the incident, the R-MWC students ordered sodas. When the drinks arrived, Ball silently slid her soda over to Miriam Gaines.

“I don’t think we were even thinking about how we could get arrested,” remembered Wolf, who spent her professional career as a United Way director, an office administrator, and a real estate agent. “It was so close to closing time, and we just felt like it was something we needed to do.”

The students quietly drank their sodas as the manager turned out the lights and closed the store. A photographer from the local newspaper was waiting outside when they left the store. “It was startling,” Wolf said. “You know you’ve done the right thing. But I don’t think we weighed any of the consequences at the time. We just did it.”

The experience, though scary at the time, helped Wolf gain confidence. “It gave me the courage to say and do what I thought was right in my life,” she said. “It was liberating to do the right thing and to know that you have a little bit of courage when you need it. I’ve taken some controversial stands in my life, and I think knowing that I did this when I was in college gave me the confidence to stand up for other issues later.”

R-MWC’s students left for winter break, leaving Quillian to manage the enduring outcry from the community. The College lost several large financial supporters over the issue. Three R-MWC trustees resigned publicly after Quillian refused to let the Board handle the decision.

“It was a difficult time,” he said. “The lines were pretty well drawn in our community. I was devoted to all of our students, and I was torn as to how best to deal with a situation like this. I respected them and I shared their concerns, but I wasn’t sure this was the best way under the circumstances to try and bring change when others were trying to bring change in a different way.”

Facing their sentence

When the students returned to campus in January, 1961, Owen and Abu-Saba faced a packed court hearing where they were found guilty and received the maximum sentence—30 days in jail. They appealed the verdict.

(Left to right) Barbara Thomas, Rebecca Mays Owen ’61, Mary Edith Bentley Abu-Saba ’61, Terrill Brumback, and James Hunter pray before heading into the courtroom in January 1961.

Abu-Saba remembers entering the courthouse on February 6, the day of their appeal, carrying a large pocketbook filled with a nightgown, clean underwear, and a toothbrush. To enter the building, they had to walk through a small path in a large, scary crowd. “There was this group of people holding tire chains as we walked down. They were really ferocious-looking, and I remember being really scared. We just walked briskly and didn’t look around too much.”

No one but their lawyer knew they were dropping their appeal, and people were shocked as the six students were led away in handcuffs. Ball remembers being in the courtroom and watching her friends face their sentence.

“The absolute point of redemption in this whole thing was that they decided Lynchburg would never change if they weren’t willing to go to jail and have the city have to deal with six college kids in jail just because they wanted to have coffee at a counter in Lynchburg together,” Ball said.

Jail proved to be boring and difficult. The two R-MWC students shared a small cell with bunk beds and a toilet in the middle of the room. Their belongings were examined, their mail opened, and the jail officials refused to allow several of their textbooks.

“It was interesting to see the jailers’ response when we visited,” Quillian said. “They couldn’t turn us away, but they didn’t quite know how to deal with it. They seemed puzzled when we showed up bringing books.”

The students passed the time studying. Abu-Saba, unable to practice for her upcoming music recitals, made a paper keyboard to rehearse. Owen wrote letters home to her family, glossing over the conditions. They were released 10 days early for good behavior and returned to campus where they tried to focus on preparing for life after college. But that spur-of-the-moment decision on a winter’s afternoon in December 1960 would ensure their lives—and the lives of many others—would never be the same.

‘I knew it was what I wanted to do. But I felt shame.’

After graduation from R-MWC, Owen, whose family was outraged at the sit-in controversy, moved to New York to earn her graduate degree. She later opened her own psychotherapy business. While she kept in touch with several of her close classmates over the years, her anger at the reaction from many in the community lingered during her adult life.

Rebecca Mays Owen ’61

Owen returned to campus in 2000 to deliver a speech for the College’s Martin Luther King Jr. event. During that speech, she vividly remembered the silence that occurred in the drugstore the afternoon the students sat down at the counter.

“It was in that moment in that drugstore I saw in their faces the mirror of something—incredibly obscene is the word that comes to mind,” she said. “Something dirty. The spectacle of white and Black students sitting at a lunch counter together. To be seen that way, to see myself in that mirror, was a strange experience. I was not ashamed of what I was doing. I knew it was what I wanted to do. But I felt shame.”

In 2002, she died after a battle with cancer.

‘I stood up for what I believed in’

Abu-Saba’s history-making decision in college was the first step in a life filled with fighting for social justice. “My part in the civil rights movement was a small one, but I stood up for what I believed in,” she said.

After graduation, she and her husband lived in Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, as well as the United States.

During that time, she became passionate about social justice issues facing the Palestinian people. She and her husband were involved in women’s rights issues, and she later became involved in the gay and lesbian marriage issue in California. She also worked with a nonprofit that helped rebuild homes and schools in Palestine.

Mary Edith Bentley Abu-Saba ’61

“You can’t deny people a place at the table,” Abu-Saba said. “It’s a spiritual response. I don’t believe we should oppress other human beings. I don’t think we are here to mistreat people. I learned some of it from home, but I also learned some of it from R-MWC. Those teachers we had, they taught this to us from books, from an intellectual point of view, and from a poignant point of view. That changed my life.”

A defining moment

Ball finds it hard to believe so many decades have passed since the sit-ins. “I never thought about that time as being brave,” she said. “But it became something I could go back to later in life. It was a thing that was so right.”

Her passions in life have revolved around righting what is wrong in the world, speaking up when others stay quiet, and empowering people to bring about change. Her work helping battered women, foster children, and young girls earned her national recognition. She has also worked as a mediator and trainer for an alternative dispute resolution center in Atlanta.

On the day of Barack Obama’s inauguration, Ball called Miriam Gaines, the African American student she shared a soda with at People’s Drug. The two women had not talked since the sit-ins.

“Looking back at it, I think I was braver than I certainly felt at the time,” Ball said. “It was a boundary I stepped across. It was a defining moment for me. It was the first time in my life that I stood up and said this isn’t right, and I can do something about it. I’m very proud to say I did. I doubt any of us ever regretted it.”

Tags: civil rights, Patterson Six, Vita No. 9