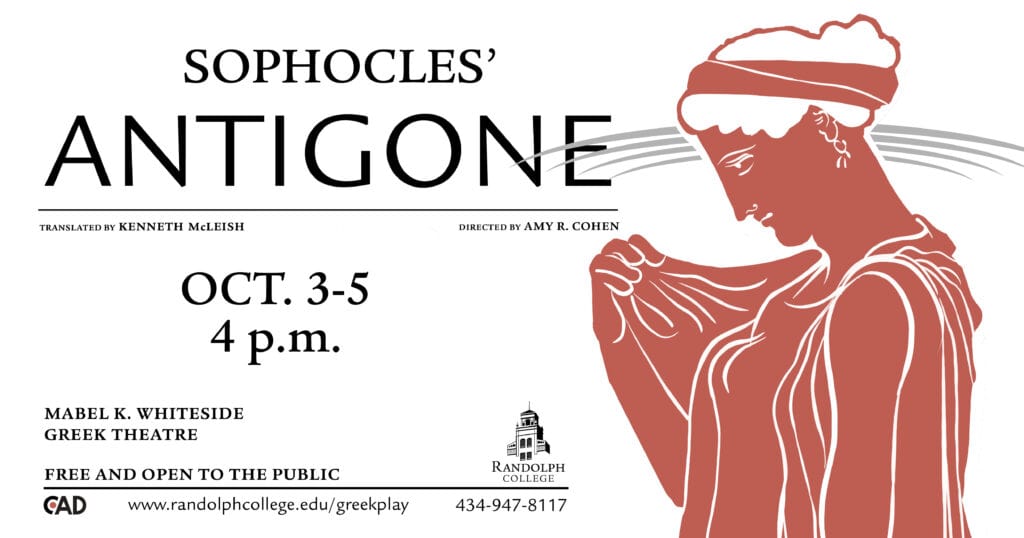

Greek Play celebrates 25 years of revived tradition

In Sophocles’ Antigone, the title character faces off with her uncle, Creon, ruler of the ancient Greek city of Thebes, over burial rites.

In Sophocles’ Antigone, the title character faces off with her uncle, Creon, ruler of the ancient Greek city of Thebes, over burial rites.

Creon’s rule follows a brutal conflict between Antigone’s brothers—Polynices, who attacked Thebes to reclaim the throne they were meant to share, and Eteocles, who defended it—both of whom died in battle.

“Creon has said that Eteocles, who was defending the city in his eyes, gets a proper burial, but Polynices, who was attacking the city, is to be left to rot on the battlefield,” explained Amy R. Cohen, who is directing Randolph’s production. “But Antigone is determined to bury him.”

The rest of the Greek tragedy follows the aftermath of Antigone defying that order and being condemned to death.

Antigone was the first Greek Play Cohen directed at the College, so it was a natural fit to bring it back in honor of the revived tradition’s 25th anniversary this year.

“It’s an honor to be part of something that has been around for as long as the Greek Play, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” said Za’Marae Morgan ’25 MFA, who plays Creon in the production. “It gives us something as a community to bond over and can bring new people into the world of theatre, introducing it in a way they’ve never experienced before.”

The free performances are scheduled for Oct. 3, 4, and 5 in Randolph’s Mabel K. Whiteside Greek Theatre, with a special panel of Greek Play alums planned at 1 p.m. Oct. 4.

The play and panel are included as part of the College’s Ancient Drama in Performance conference. The conference brings scholars from across the nation and is hosted by Randolph’s Center for Ancient Drama.

The Greek Play tradition dates back to 1909, when Greek professor Mabel K. Whiteside staged Euripides’ tragedy Alcestis at the College. Productions continued annually until her retirement in 1954.

Cohen revived the tradition in 2000, determined to adhere to the conventions that governed ancient theatre. Among them: Three actors typically play all of the main roles, without microphones, and all performers wear hand-crafted masks.

For Morgan, the experience has been full of growth.

“As an actor, I didn’t realize how much I rely on my facial expressions to convey emotions,” he said. “While it’s been a learning curve, it did provide me with an opportunity to discover all the ways Creon would move in a space and react to information. This has been fun because I could lean more into the physicality of the character to get those emotions across to the audience.”

During the first four productions under Cohen, the masks—then made of papier-mâché or plaster caste material—only covered half of a performer’s face. She still laughs about the cheap doll wigs they used for hair in that first production.

Techniques and materials were refined over the years; the wigs were replaced by yarn, and in 2006, they began using full theatrical masks developed during a Summer Research Program project.

Today, they scan the actors’ faces and use the College’s 3D printer to create molds. The actual masks are then made using layers of linen and glue.

“That technique, layering linen, is actually a well-known ancient technology used in armor,” Cohen said.

Cohen and her team have been working on the production since last spring, with auditions, a read-through, and then weeks of rehearsals once classes were in session.

“My feeling since really early on has been that I’ve been given a laboratory—an artistic lab where we get to try out our theories about what the Greek playwrights accomplished and how they did it,” Cohen said “If we do our plays the way they did, what more do we understand about the plays?

“I hope with every show that even if someone comes in thinking they’re just going to see something preserved in amber, that that is not actually how they leave,” she added. “That we do entertain them just like Sophocles and Euripides and Aristophanes did in their time. We want to give them an authentic experience.”

Tags: classics, greek play