Student Success Summit looks at challenges faced by first-generation, lower-income students

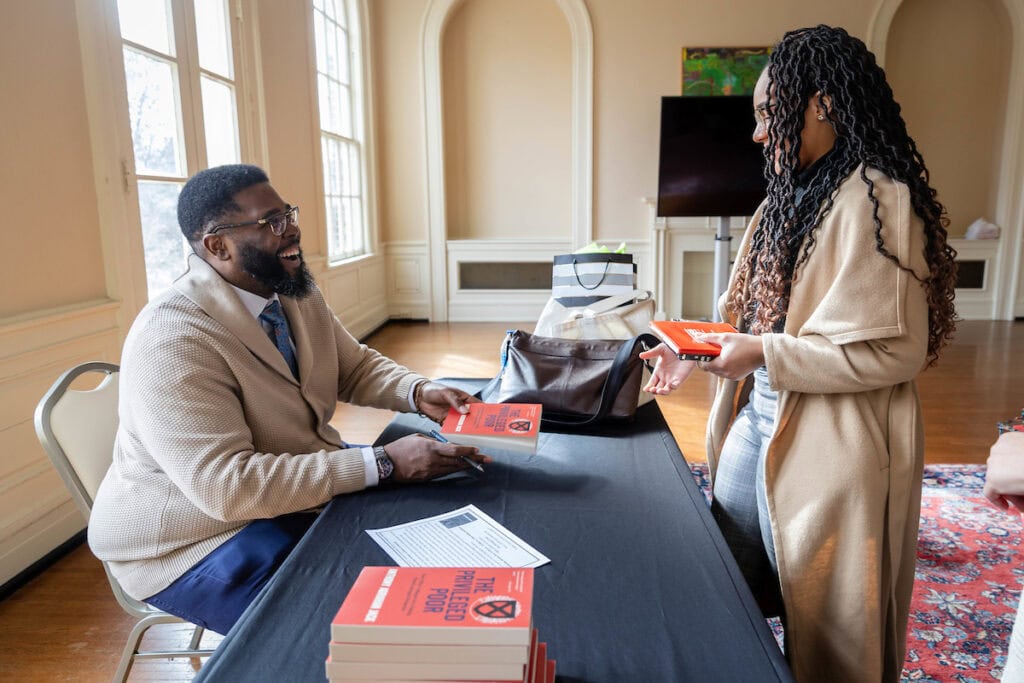

Anthony Abraham Jack speaks during Randolph’s 2nd Student Success Summit on Wednesday, Jan. 31.

College comes with a lot of expectations, including the idea that if a student needs help, he or she will ask for it.

But this doesn’t take students’ diverse backgrounds into account, Anthony Abraham Jack told faculty and staff who gathered for Randolph’s 2nd Student Success Summit on Wednesday.

“Colleges expect students to be comfortable and proactive in forging relationships with faculty from the moment they step foot on campus,” said Jack, a professor of higher education leadership at Boston University and the inaugural faculty director of the Newbury Center, which supports first-generation students.

“This is the road to letters of recommendations, internships, invitations to special dinners, to coveted events,” he said. “This is the road to emotional support when times get tough.”

Yet this expectation often remains unsaid, leading to culture shock among some first-generation and lower-income college students, for whom one size does not fit all.

“Lower-income students have shared beginnings but live ever more divergent lives before coming to college,” he said. “We must examine where students come from and what they have been through to understand why they chart the paths they do once they reach our gates. To overlook the rich diversity of experience among lower-income and first-generation college students is then to base policy and university practices on only a partial picture.”

In his book, The Privileged Poor: How Elite Colleges Are Failing Disadvantaged Students, Jack divided those students into two groups: the doubly disadvantaged, who enter college from local, typically distressed public high schools, and the privileged poor, who come from similar economic backgrounds but attended boarding, day, and preparatory high schools.

Jack signed copies of “The Privileged Poor” after talking to faculty and staff. His second book project, looking at how the pandemic affected disadvantaged students, is due out this summer.

“Social science research did not make space for these experiences as part of the larger first-generation, lower-income student narrative,” said Jack, a first-generation student himself. “When they wrote about us, they wrote of a single experience of culture shock and isolation for a group of ‘students at risk.’”

During Wednesday’s talk, he shared the stories of students he interviewed in his research.

One student came from a chaotic high school experience, where her teachers “exhausted themselves maintaining order. There was often nothing left in the tank for making connections.”

Her college transition was difficult, contradicting everything she knew from her life back home. She’d never heard the term office hours and, even when her professors encouraged students to make contact, she was too intimidated to seek out that help.

“It’s the story behind why,” Jack said. “For her, hunkering down and doing things on her own was the right way to get ahead.”

He contrasted her story with that of a student who came from a similar neighborhood but attended an affluent boarding school. That student felt comfortable approaching her professors, telling Jack, “It’s actually my right.”

Institutions, he said, mistakenly see students like the latter as engaged, and assume the former is OK simply because she’s not seeking out any resources.

“We must be more proactive in how we give help,” he said. “Those for whom the college experience is new should not be the only ones forced to grow, to change, to adapt.”

Jack’s research also looked at food insecurity on college campuses, and how it’s heightened for some students during breaks when the dining halls and eateries are closed.

Even among the schools that were most progressive with their financial aid, he found that only 18 percent kept their dining halls open during spring break without restrictions.

It’s an example of opening the gates, he added, but forgetting to keep them open for the students who couldn’t afford to leave.

It was something Jack experienced during his own college days. As a lower-income, first-generation college student at Amherst College in Massachusetts, he worked four jobs to get by and didn’t think rest was a luxury he could afford.

“This is not just what I study,” he said. “It’s what I lived.”

New students require taking on new responsibilities, and Jack said colleges must move from access to inclusion.

“Institutions have forgotten the old, albeit universal truth, that citizenship is so much more than just being in a place. It’s about accessing all of the rights and privileges pertaining thereto,” he said.

“We must work to ensure that students don’t just get in and graduate, but do so whole and healthy and ready for the next adventure.”

Tags: student success summit